Jan Hus

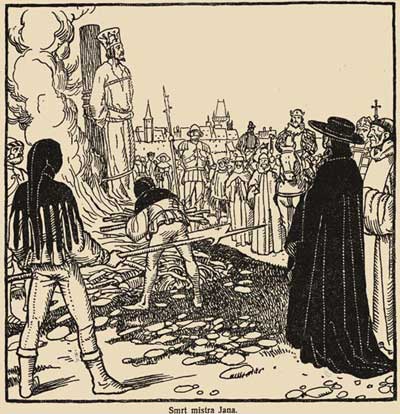

Jan Hus ( burned at the stake just like Joan of Ark )

|

Jan Hus, who was originally known as John of Husinec, became one of the greatest personalities in Czech history. He gave all his knowledge, abilities and strengths to serving the just cause of the common people. Hus constantly encouraged the ordinary believer’s self-confidence and courage. Jan Hus was born on July 6, 1369 in the village of Husinec, in Southern Bohemia which is now in the Czech Republic. He attended Prague University where he studied theology. As a poor student at Prague University, he became familiar with the hard life of the common people. He was close to them, realized the extent of their sufferings, and was never estranged from them. He wrote: “When I was a student they often sang vigils in the church. While we were singing, the priests collected money from the congregation and thus misused us.” His rebellion against authority and his unyielding devotion to his belief led to his death. Hus supported himself by singing and serving in the churches. His conduct was exemplary and his devotion to study remarkable. In 1393 Hus received his Bachelor of Arts degree and in 1396 he received his Master’s degree. He was ordained a priest in 1400 and became rector of the university in 1402 – 1403. He was also appointed preacher in the newly erected Bethlehem Chapel and was made head of the theological faculty of the university. The Bethlehem Chapel was built so the gospel could be proclaimed in the language of the people. Services at the Bethlehem Chapel were conducted in Czech contrary to the common practice of conducting in Latin. He realized that the practices of the Roman Church were not according to the teachings of Christ and therefore condemned those practices in his preaching and writing. Jan Hus was a strong partisan on the side of the Czechs, and hence of the Realists. He was greatly influenced by the writing of the early English reformer John Wycliff, though he did not agree with all of Wycliff’s teachings. It seemed to him that the English Thinker was expressing just what he himself felt. It was mainly Wycliff’s principle that the “sinful authority ceases to be an authority” that aroused Hus’s enthusiasm. Wycliff’s criticism of the Church in England had much in common with Hus’s critical views of Church and society in Bohemia. Hus was so drawn to Wycliff’s work that he made it a theoretical basis of his own critical writings. Jan Hus encouraged the ordinary believer’s self-confidence and courage. He preached actively against the worst abuses of the Roman Catholic Church of the day. His primary teachings called for a higher level of morality among the priesthood because financial abuses, sexual immorality, and drunkenness were common among the priests of Europe. His teachings also called for preaching and Bible reading in the common language and for all Christians to receive full communion. At the time, lay persons received only the bread during communion, and only priests were allowed to receive the wine. Among his teachings were the oppositions of the sale of indulgences. Those were documents of personal forgiveness from the Pope which were sold for sometimes exorbitant prices to raise funds for crusades. Hus also opposed the relatively new doctrine of Papal infallibility when Papal decrees contradicted the Bible. He asserted the primary of the scriptures over church leaders and councils. In one sermon, for instance, Hus compared the wretched peasant or a poor old woman with a wealthy and sinful lord or prelate. He concluded that the peasant and the old woman, each living a virtuous life, stood higher before Christ than any nobleman or even prince and king. Soon after hearing this, the Czech prelates took steps to silence Hus. They knew that with Hus demanding complete poverty for the Church that their material interests would be endangered. Therefore, at first, the Archbishop of Prague banned Wycliff’s writings, and anyone who defended him was to be persecuted as a heretic. In any event, by that time Hus already had the support of the people of Prague. He handed over his copies of Wycliff’s writings, which were publicly burned, but he went on proclaiming his devotion to Wycliff’s work and defending it faithfully. The conflict between Hus and the prelates, led by the Archbishop of Prague, climaxed in 1412. The Pope was then at war with the King of Naples and was, therefore, in need of a great deal of money. So he decided to sell indulgences publicly to all Christians. “Everybody who bought indulgences for a certain sum was forgiven his sins and then could buy himself an after-life in Paradise instead of in hell.” Hus severely criticized the Pope's action. After this struggle against the sale of indulgences Hus had to leave Prague. His friends feared for his life because he was excommunicated and no Christian was allowed to give him food, drink, or a place to stay. Hus went to Southern Bohemia, for Kozi Hradek where he continued his literary work as well as his sermons. He preached to the people under a linden tree in front of Kozi Hradek. Crowds of peasants came from far and near, gathering around him looking for a way out of their misery and poverty. Hus increased his attacks against the prelates and against all who exploited the “villein” population. He was firmly convinced that he defended God’s truth, which was the truth for the common laboring people.

6. 7. 1415 Hus was invited to appear before the Council of Constance and did not hesitate to accept the invitation. Hus’s criticisms and calls for reform led to his journey to the Council of Constance in order to defend his beliefs. Soon after Hus’s arrival at the Council, he was arrested and thrown into prison. In the winter of 1414, he was carried away to the castle of Gottlieben, where, with hands and feet in fetters, he lay in a tower exposed to cold winds. His letters from Constance, which he wrote in prison and sent to Bohemia, are filled with faith and the love of his native country and of the Czech people. In one of those letters, known as his Final Declaration, he stated, “I, Jan Hus, in hope a priest of Jesus Christ, fearing to offend God, and fearing to fall into perjury, do hereby profess my willingness to abjure all or any of the articles produced against me by false witnesses. For God is my witness that I neither preached, affirmed, nor defended them though they way that I did. Moreover, concerning the articles that they have extracted from my books, I say that I detest any false interpretation, which any of them bears. But in as much as I fear to offend against the truth, or to gainsay the opinion of the doctors of the church, I cannot abjure any one of them, And if it were possible that my voice could now reach the whole world, as at the Day of Judgement every lie and every sin that I have committed will be made manifest, then would I gladly abjure before all the world every falsehood and error which I either had thought of saying or actually said! I say I write this of my own free will and choice. Written with my own hand, on the first day of July.” Even on July 6, 1415 when led through the streets of Constance in a shameful procession to the stake, Jan Hus remained calm and of good cheer. He was tied to a stake and was facing east toward Jerusalem, the symbol of the heavenly city. When a priest realized “a grave mistake”, Hus was untied and turned to face the west, the future home of Protestantism. While bound to the stake, Hus said, “The prime endeavor of all my preaching, teaching, and writing and all of my deeds has been to turn people from their sins and this truth that I have written, taught and preached in accordance with the word of God and the teaching of the holy doctors I willingly seal with my death today.”

Jan Hus monument (statue) at the Old Town Square After Hus’ death, the Hussite movement became even more popular and expanded into all of Moravia and Bohemia. Almost the entire population of the region became Hussite. This included many Germans. This unity became the largest denomination in the area, at one time totaling about a quarter million believers. After years of spiritual struggles with powers of the counter- reformation, the Hussite movement weakened inside and out. The execution of the Czech “heretic” Jan Hus, perpetuated the religious dissent in Bohemia, which also created nationalist tendencies in religious music. One of the most important parts of the Council Constance was that it brought together music and musicians from all over Europe. Jan Hus was on the threshold of the new era, which within a century of his

death resulted in the Reformation. Hus’ strict moral stature, devotion

to the truth as he knew it, integrity of character, and loyalty to the Church

were all indeed inspirational to the people during this time. He was a leader

among leaders. |

Hussite Wars

Charles University

Other famous people & artists

Back